Rabbit Working to Get Site Hopping Again

Peter Lancaster has ever had a dear for rabbits. But when he first saw a pygmy rabbit – perhaps what would become the most influential brute throughout his life – he didn't know what it was.

Ane spring interruption as a kid, Lancaster went camping with a few friends a petty means from his dwelling house in East Wenatchee.

Out in the sage, they saw this little creature.

"We looked at information technology, and we all said … Pika?" Lancaster recalls.

But 12-year-erstwhile Lancaster decided they hadn't quite identified the cute animate being with rounded ears. It hopped off into a burrow.

Decades afterwards, Lancaster saw more pygmy rabbits in Dillion, Mont. And he knew the creature outside his hometown in central Washington had been a baby, no bigger than a baseball game. (They're the smallest rabbit species in North America.)

That began years of piece of work to try and save the species, now endangered in Washington.

"They have evolved into existence the perfect denizen of the sagebrush steppe," Lancaster says. "If this animal really doesn't demand annihilation except a place to live – and it'due south nigh to go extinct – something is wrong. Something has happened that will probably touch united states of america."

Genetically distinct

The rabbits in Washington'due south Columbia Basin are genetically distinct. In 2001, only 16 pygmy rabbits were known to exist in the state. Large recovery efforts accept taken place in the Sagebrush Apartment Wildlife Area, most Ephrata, and Beezley Hills, near Quincy.

On a camping trip near Beezley Hills in 1998, Lancaster spied a previously unknown pygmy rabbit colony.

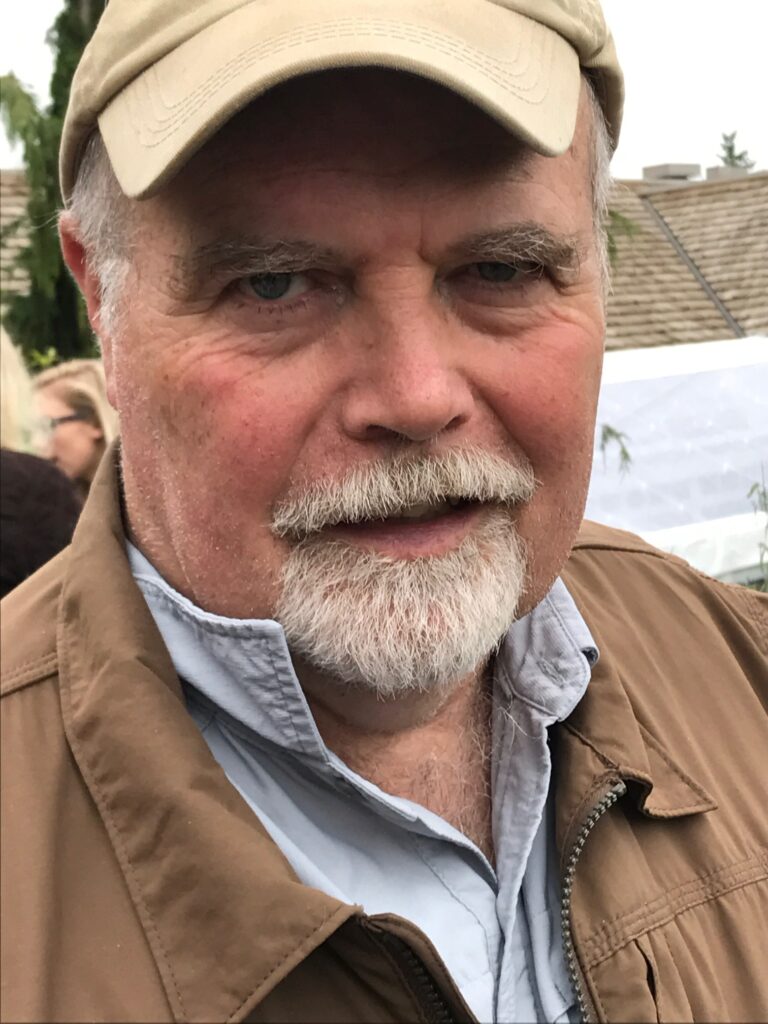

Peter Lancaster has been working to preserve pygmy rabbit habitat in Washington for years, which he traces back to first seeing one on a camping ground trip every bit as kid most East Wenatchee. Courtesy of Peter Lancaster

He'd recently left his chore at Microsoft and began volunteering for pygmy rabbit surveys, where he began to understand their habitat needs.

"I merely kind of ransacked all the places I'd gone to in my youth and thought possibly in that location were rabbits there," he says.

For about a yr, he'd scour maps for platonic habitat and get in search. His efforts paid off.

"I was ecstatic. It's kind of hard to explain because I had been searching for such a long fourth dimension. Then, when I saw this burrow with all this bed of pellets, I was on cloud nine," Lancaster says.

He shot a quick video, and that's about when he heard a road grader in the distance. The land was going to be parceled and sold.

Wrangling help

Lancaster tried to wrangle aid from conservation organizations and the land, but the land sale was moving too speedily. And so he bought information technology himself.

He wasn't really interested in owning the land. He just wanted to protect the rabbits.

"That was well-nigh 25 years ago. Information technology became a mainstay for breeding operations in the Beezley Hills area," Lancaster says.

As the program gained success, another bundle went up for auction.

He called his best friend, Paul Schuster, who also worked at Microsoft and was a conservationist at heart. The two had enjoyed whitewater kayaking adventures and trips around the earth together. Now, it seemed, they'd exist co-landowners.

The new land was an old Conservation Reserve Programme field, former wheat that hadn't been harvested since the mid-1980s. As it turned out, the rabbits really liked the habitat.

Peter Lancaster (left) and Paul Schuster traveled the globe together and co-owned land to conserve for pygmy rabbits. Here, they're on a safari in Tanzania. Courtesy of Peter Lancaster

Schuster, who died unexpectedly final twelvemonth after an blow, ever knew he wanted to donate the land to The Nature Conservancy , which helps with the breeding program at Beezley Hills.

Lancaster knew he wanted to laurels his friend.

"(Schuster) bought the belongings because I asked him. He had no interest, except for conservation," Lancaster says. "But information technology'due south but because I asked him as a friend to practice it, that he did it. It was completely selfless."

Disquisitional country after fires

Final month, Lancaster and the estate of Paul Schuster donated 282 acres to The Nature Conservancy. The state was surrounded past the conservancy'due south property, which helped the system "complete a critical piece of the puzzle," says Corinna Hanson, Moses Coulee State Manager with TNC.

"It lies right in ane of the almost important areas for the recovery of the species," Hanson says.

The land is becoming even more than disquisitional as fires have torched much of the pygmy rabbit habitat in contempo years. Other threats include habitat fragmentation and an emerging rabbit hemorrhagic disease – "like rabbit ebola," co-ordinate to biologist Jon Gallie. It'southward been plant in wild jackrabbits every bit recently every bit March most Boise. Biologists are vaccinating captive pygmy rabbits, which will delay releases this yr.

In 2017, the Sutherland Canyon Burn down burned through the offset tract of land Lancaster had purchased. It destroyed a ix-acre convict breeding pen and killed many rabbits, virtually likely including 1 special rabbit Lancaster named Jade.

"He or she typified many pygmies I've seen in the field. They accept an aura of serenity. Of course, that is anthropomorphizing, only I'll willingly admit to having a bias as far as pygmy rabbits go," Lancaster says.

The fall 2020 Pearl Hill Fire burned through more than pygmy rabbit habitat. Washington Department of Fish and Wild fauna biologist Jon Gallie says the fire absolutely devastated an area most Jameson Lake they'd hoped would become "the truthful shining star."

Peter Lancaster and the estate of Paul Schuster donated 282 acres of prime pygmy rabbit habitat to The Nature Salvation. Lancaster called this rabbit Jade. Courtesy of Peter Lancaster

Biologist Jon Gallie says they'd been able to save some rabbits that had survived inside their burrows during the 2017 fire. A day afterward the Pearl Hill fire burned through the prime habitat, they rushed with supplies, hoping to rescue every bit many animals as possible.

"Correct away, information technology was a very different feeling. There was no rapid motion when we got in there. There wasn't anything left. It was all vaporized ash," Gallie recalls. "In fact, almost of the burrows were completely filled with this sand and ash from the firestorm."

Every rabbit had been lost. That basically amounted to half the pygmy rabbits biologists could account for in Washington. Almost worse, the entire habitat was burned to a well-baked.

Pygmy rabbits need mature sagebrush to survive. Gallie says if the bushes aren't at least iii feet tall – the sagebrush should exist difficult for humans to walk in – don't count on seeing a tiny rabbit. He says information technology volition be at to the lowest degree 15 years earlier they tin can use that habitat again.

"We had to tear these pages out of the recovery plan, like, we're done," Gallie says. "We have to wait 15 years before we can come back in hither and recalibrate. … It'southward really hard to not let your mind wander (and think): Is this even possible? Are we going to do all this work and in three more years have some other fire?"

Lancaster says burn down has wiped out all the locations he'd planned to continue searching for unknown pygmy rabbit colonies. For example, the 2019 fire on Rattlesnake Mountain nigh Hanford.

"That was an area that I was about to get to, to expect for pygmy rabbits, and it burned. So I was like, 'Well, that'southward not an option anymore.' I had a whole agglomeration of areas sort of singled out where I wanted to wait, just they all burned," he says.

Withal hoping for hopping

Lancaster holds out hope to run across pygmy rabbits hopping again. Recently, biologists discovered a colony outside Sagebrush Flat. A bunch of rabbits had hopped away from the colony where they were built-in and created an all-encompassing new living space. The dispersal was an unexpected sign of promise for biologists, who'd been searching over miles for any sign of pygmy rabbits.

Many of the sagebrush in this Moses Coulee area of primal Washington were burned to a crisp during the September 2020 Pearl Loma Burn. It tin can take decades for sagebrush to fully recover after an extremely intense wildfire. CREDIT: Courtney Flatt/NWPB

"Information technology kind of brought us back from the brink of extinction," Gallie says.

They'd had to pivot later the 2020 fires and almost couldn't believe their luck when they searched some private land (with permission of the landowner). They were three miles from the closest known active couch and upwards to five mile from any release site.

The more than they looked, the more they found. Rabbits carrying on as rabbits do.

In all, they'd establish more than sixty active burrows.

"It'due south really turned our understanding of habitat connectivity and landscape ecology and recalibrated what nosotros're thinking these animals are going to be capable of because they didn't simply disperse and colonize the next available habitat," Gallie says.

In the Beezley Hills surface area, where Lancaster is altruistic land, Gallie says the rabbit populations passed a critical point this winter. In that location now seems to be enough pygmy rabbits in the wild that the population is starting to sustain itself.

"Nature does information technology better than we are ever going to," Gallie said. "I wouldn't say we're home complimentary and established, merely it has a very different feel this year."

As a 5th-generation Washingtonian, Lancaster hopes future generations will see the joy in these tiny rabbits that he's experienced. He calls them a "heritage of Washington state."

Sometimes Lancaster imagines his keen-smashing grandfather hauling freight from Walla Walla due north toward Spokane.

"I only wondered what he saw before all of that property was put nether turn," Lancaster says. "I just wanted some hereafter person to have the opportunity to encounter what I saw. And the just manner to do that is through preservation."

Source: https://www.nwpb.org/2021/04/11/hoping-for-hopping-how-a-tiny-rabbit-united-friends-and-conservation-in-central-washington/

0 Response to "Rabbit Working to Get Site Hopping Again"

Post a Comment